gentoo.LinuxHowtos.org

$Revision: 1.2 $, $Date: 2003/11/08 14:37:43 $

Copyright © 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003 Giles Orr

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under

the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later

version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant

Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy

of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation

License".

Abstract

Creating and controlling terminal and xterm prompts is discussed,

including incorporating standard escape sequences to give username,

current working directory, time, etc. Further suggestions are made

on how to modify xterm title bars, use external functions to provide

prompt information, and how to use ANSI colours.

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction and Administrivia

- 2. Bash and Bash Prompts

- 3. Bash Programming and Shell Scripts

- 4. External Commands

- 5. Saving Complex Prompts

- 6. ANSI Escape Sequences: Colours and Cursor Movement

- 7. Special Characters: Octal Escape Sequences

- 8. The Bash Prompt Package

- 9. Loading a Different Prompt

- 10. Loading Prompt Colours Dynamically

- 11. Prompt Code Snippets

- Built-in Escape Sequences

- Date and Time

- Counting Files in the Current Directory

- Total Bytes in the Current Directory

- Checking the Current TTY

- Stopped Jobs Count

- Load

- Uptime

- Number of Processes

- Controlling the Size and Appearance of $PWD

- Laptop Power

- Having the Prompt Ignored on Cut and Paste

- New Mail

- Prompt Beeps After Long-Running Commands

- 12. Example Prompts

- A. GNU Free Documentation License

Table of Contents

I've been maintaining this document for nearly six years (I believe

the first submitted version was January 1998). I've received a lot of

e-mail, almost all of it positive with a lot of great suggestions, and I've

had a really good time doing this. Thanks to everyone for the support,

suggestions, and translations!

I've had several requests both from individuals and the LDP group to issue

a new version of this document, and it's long past due (two and a half years

since the last version) - for which I apologize. Converting this monster

to DocBook format was a daunting task, and then when I realized that I

could now include images, I decided I needed to include all the cool

examples that currently reside on my homepage. Adding these is a slow

process, especially since I'm improving the code as I go, so only a few are

included so far. This document will probably always feel incomplete to me

... I think however that it's reasonably sound from a technical point of

view (although I have some mailed in fixes that aren't in here yet

- if you've heard from me, they'll get in here eventually) so I'm going to

post it and hope I can get to another version soon.

One other revision of note: this document (as requested by the LDP) is now

under the GFDL. Enjoy.

Revision History Revision v0.93 2003-11-06 Â

Removal of very outdated "Translations" section.

Revision v0.92 2003-11-06 Â

Added section on line draw in RXVT.

Revision v0.91 2002-01-31 Â

Fixed text and code to "Total Bytes" snippet.

Revision v0.90 2001-08-24 go Added section on screen and Xterm titlebars.

Revision v0.89 2001-08-20 go Added clockt example, several example images added,

improved laptop power code, minor tweaks. Revision v0.85 2001-07-31 go Major revisions, plus change from Linuxdoc to DocBook.

Revision v0.76 1999-12-31 go Revision v0.60 1998-01-07 go Initial public release?

You will need Bash. This should be easy: it's the default shell for just

about every Linux distribution I know of. The commonest version is now

2.0.x. Version 1.14.7 was the standard for a long time, but that started

to fade around 2000. I've been using Bash 2.0.x for quite a while now. With

recent revisions of the HOWTO (later than July 2001) I've been using a lot

of code (mainly ${} substitutions) that I believe is specific to 2.x and

may not work with Bash 1.x. You can check your Bash version by typing

echo $BASH_VERSION at the prompt. On my machine, it

responds with 2.05a.0(1)-release.

Shell programming experience would be good, but isn't essential: the more

you know, the more complex the prompts you'll be able to create. I assume

a basic knowledge of shell programming and Unix utilities as I go through

this tutorial. However, my own shell programming skills are limited, so I

give a lot of examples and explanation that may appear unnecessary to an

experienced shell programmer.

I include a lot of examples and explanatory text. Different parts will be

of varying usefulness to different people. This has grown long enough that

reading it straight through would be difficult - just read the sections you

need, backtrack as necessary.

This is a learning experience for me. I've come to know a fair bit about

what can be done to create interesting and useful Bash Prompts, but I need

your input to correct and improve this document. I no longer make code

checks against older versions of Bash, let me know of any incompatibilities

you find.

The latest version of this document should always be available at

http://www.gilesorr.com/bashprompt/ (usually only in HTML

format). The latest official release should always be at http://www.tldp.org/. Please

check these out, and feel free to e-mail me at <giles at dreaming

dot org> with suggestions.

I use the Linux Documentation Project HOWTOs almost exclusively in the HTML

format, so when I convert this from DocBook SGML (its native format), HTML

is the only format I check thoroughly. If there are problems with other

formats, I may not know about them and I'd appreciate a note about them.

There are issues with the PDF and RTF conversions (as of December 2000),

including big problems with example code wrapping around the screen and

getting mangled. I always keep my examples less than 80 characters wide,

but the PDF version seems to wrap around 60. Please use online examples if

the code in these versions don't work for you. But they do look very

pretty.

This is a list of problems I've noticed while programming prompts. Don't

start reading here, and don't let this list discourage you - these are

mostly quite minor details. Just check back if you run into anything odd.

Many Bash features (such as math within $(()) among others) are

compile time options. If you're using a binary distribution such as comes

with a standard Linux distribution, all such features should be compiled

in. But if you're working on someone else's system, this is worth keeping

in mind if something you expected to work doesn't. Some notes about this

in Learning the Bash Shell second edition, p.260-262.

The terminal screen manager "screen" doesn't always get along with ANSI

colours. I'm not a screen expert, unfortunately. Versions older than

3.7.6 may cause problems, but newer versions seem to work well in all

cases. Old versions reduce all prompt colours to the standard foreground

colour in X terminals.

Xdefaults files can override colours. Look in

~/.Xdefaults for

lines referring to XTerm*background

and XTerm*foreground (or possibly

XTerm*Background and

XTerm*Foreground).

One of the prompts mentioned in this document uses the output of

"jobs" - as discussed at that time, "jobs" output to a pipe is broken in

Bash 2.02.

ANSI cursor movement escape sequences aren't all implemented in all X

terminals. That's discussed in its own section.

Some nice looking pseudo-graphics can be created by using a VGA font

rather than standard Linux fonts. Unfortunately, these effects look awful

if you don't use a VGA font, and there's no way to detect within a term

what kind of font it's using.

Things that work under Bash 1.14.7 don't necessarily work the

same under 2.0+, or vice versa.

I often use the code PS1="...\\$${NO_COLOUR} " at

the end of my PS1 string. The \\$ is

replaced by a "$" for a normal user, and a "#" if you are root, and the

${NO_COLOUR} is an escape sequence that stops any colour

modifications made by the prompt. However, I've had problems seeing the

"#" when I'm root. I believe this is because Bash doesn't like two dollar

signs in a row. Use PS1="...\\$ ${NO_COLOUR}"

instead. I'm still trying to figure out how to get rid of that extra

space.

In producing this document, I have borrowed heavily from the work of the

Bashprompt project, which was at http://bash.current.nu/. This site

was removed from its server as of July 2001 but Robert Current, the admin,

assured me it would reappear soon. Unfortunately, it appears he's now (May

2003) let his domain registration lapse. The work of that project is

carried on indirectly by Bashish

(http://bashish.sourceforge.net/), with whom I've had no contact.

Other sources used include the xterm Title mini-HOWTO

by Ric Lister, available at

http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/mini/Xterm-Title.html, Ansi

Prompts by Keebler, available at

http://www.ncal.verio.com/~keebler/ansi.html (now deceased),

How to make a Bash Prompt Theme by Stephen Webb,

available at

http://bash.current.nu/bash/HOWTO.html (also deceased), and

X ANSI Fonts by Stumpy, available at

http://home.earthlink.net/~us5zahns/enl/ansifont.html.

Also of immense help were several conversations and e-mails from Dan,

who used to work at Georgia College & State University, whose knowledge

of Unix far exceeded mine. He gave me several excellent suggestions,

and ideas of his have led to some interesting prompts.

Three books that have been very useful while programming prompts are

Linux in a Nutshell by Jessica Heckman Perry

(O'Reilly, 3rd ed., 2000), Learning the Bash Shell by

Cameron Newham and Bill Rosenblatt (O'Reilly, 2nd ed., 1998) and

Unix Shell Programming by Lowell

Jay Arthur (Wiley, 1986. This is the first edition, the fourth came out in

1997).

Table of Contents

Descended from the Bourne Shell, Bash is a GNU product, the

"Bourne Again

SHell." It's the standard command line interface on

most Linux machines. It excels at interactivity, supporting command line

editing, completion, and recall. It also supports configurable prompts -

most people realize this, but don't know how much can be done.

Most Linux systems have a default prompt in one colour (usually gray) that

tells you your user name, the name of the machine you're working on, and

some indication of your current working directory. This is all useful

information, but you can do much more with the prompt: all sorts of

information can be displayed (tty number, time, date, load, number of

users, uptime ...) and the prompt can use ANSI colours, either to make it

look interesting, or to make certain information stand out. You can also

manipulate the title bar of an Xterm to reflect some of this information.

Beyond looking cool, it's often useful to keep track of system information.

One idea that I know appeals to some people is that it makes it possible to

put prompts on different machines in different colours. If you have

several Xterms open on several different machines, or if you tend to forget

what machine you're working on and delete the wrong files (or shut down the

server instead of the workstation), you'll find this a great way to

remember what machine you're on.

For myself, I like the utility of having information about my machine

and work environment available all the time. And I like the challenge of

trying to figure out how to put the maximum amount of information into the

smallest possible space while maintaining readability.

Perhaps the most practical aspect of colourizing your prompt is the

ability to quickly spot the prompt when you use scrollback.

The appearance of the prompt is governed by the shell variable PS1.

Command continuations are indicated by the PS2 string, which can be

modified in exactly the same ways discussed here - since controlling it is

exactly the same, and it isn't as "interesting," I'll mostly be modifying

the PS1 string. (There are also PS3 and PS4 strings. These are never seen

by the average user - see the Bash man page if you're interested in their

purpose.) To change the way the prompt looks, you change the PS1 variable.

For experimentation purposes, you can enter the PS1 strings directly at the

prompt, and see the results immediately (this only affects your current

session, and the changes go away when you exit the current shell). If you

want to make a change to the prompt permanent, look at the section below

the section called "Setting the PS? Strings Permanently".

Before we get started, it's important to remember that the PS1 string is

stored in the environment like any other environment variable. If you

modify it at the command line, your prompt will change. Before you make

any changes, you can save your current prompt to another environment

variable:

[giles@nikola giles]$ SAVE=$PS1

[giles@nikola giles]$

The simplest prompt would be a single character, such as:

[giles@nikola giles]$ PS1=$

$ls

bin mail

$

This demonstrates the best way to experiment with basic prompts, entering

them at the command line. Notice that the text entered by the user

appears immediately after the prompt: I prefer to use

$PS1="$ "

$ ls

bin mail

$

which forces a space after the prompt, making it more readable. To restore

your original prompt, just call up the variable you stored:

$ PS1=$SAVE

[giles@nikola giles]$

There are a lot of escape sequences offered by the Bash shell for

insertion in the prompt. From the Bash 2.04 man page:

When executing interactively, bash displays the primary

prompt PS1 when it is ready to read a command, and the

secondary prompt PS2 when it needs more input to complete

a command. Bash allows these prompt strings to be cus-

tomized by inserting a number of backslash-escaped special

characters that are decoded as follows:

\a an ASCII bell character (07)

\d the date in "Weekday Month Date" format

(e.g., "Tue May 26")

\e an ASCII escape character (033)

\h the hostname up to the first `.'

\H the hostname

\j the number of jobs currently managed by the

shell

\l the basename of the shell's terminal device

name

\n newline

\r carriage return

\s the name of the shell, the basename of $0

(the portion following the final slash)

\t the current time in 24-hour HH:MM:SS format

\T the current time in 12-hour HH:MM:SS format

\@ the current time in 12-hour am/pm format

\u the username of the current user

\v the version of bash (e.g., 2.00)

\V the release of bash, version + patchlevel

(e.g., 2.00.0)

\w the current working directory

\W the basename of the current working direc-

tory

\! the history number of this command

\# the command number of this command

\$ if the effective UID is 0, a #, otherwise a

$

\nnn the character corresponding to the octal

number nnn

\\ a backslash

\[ begin a sequence of non-printing characters,

which could be used to embed a terminal con-

trol sequence into the prompt

\] end a sequence of non-printing characters

For long-time users, note the new \j and

\l sequences: these are new in 2.03 or 2.04.

Continuing where we left off:

[giles@nikola giles]$ PS1="\u@\h \W> "

giles@nikola giles> ls

bin mail

giles@nikola giles>

This is similar to the default on most Linux distributions. I wanted a

slightly different appearance, so I changed this to:

giles@nikola giles> PS1="[\t][\u@\h:\w]\$ "

[21:52:01][giles@nikola:~]$ ls

bin mail

[21:52:15][giles@nikola:~]$

Various people and distributions set their PS? strings in different places.

The most common places are /etc/profile, /etc/bashrc, ~/.bash_profile, and

~/.bashrc . Johan Kullstam (johan19 at idt dot net) writes:

the PS1 string should be set in .bashrc. this is because

non-interactive bashes go out of their way to unset PS1. the bash man

page tells how the presence or absence of PS1 is a good way of knowing

whether one is in an interactive vs non-interactive (ie script) bash

session.

the way i realized this is that startx is a bash script. what this

means is, startx will wipe out your prompt. when you set PS1 in

.profile (or .bash_profile), login at console, fire up X via startx,

your PS1 gets nuked in the process leaving you with the default

prompt.

one workaround is to launch xterms and rxvts with the -ls option to

force them to read .profile. but any time a shell is called via a

non-interactive shell-script middleman PS1 is lost. system(3) uses sh

-c which if sh is bash will kill PS1. a better way is to place the

PS1 definition in .bashrc. this is read every time bash starts and is

where interactive things - eg PS1 should go.

therefore it should be stressed that PS1=..blah.. should be in .bashrc

and not .profile.

I tried to duplicate the problem he explains, and encountered a

different one: my PROMPT_COMMAND variable (which will be introduced later)

was blown away. My knowledge in this area is somewhat shaky, so I'm going

to go with what Johan says.

Table of Contents

I'm not going to try to explain all the details of Bash scripting in a

section of this HOWTO, just the details pertaining to prompts. If you want

to know more about shell programming and Bash in general, I highly

recommend Learning the Bash Shell by Cameron Newham

and Bill Rosenblatt (O'Reilly, 1998). Oddly, my copy of this book is quite

frayed. Again, I'm going to assume that you know a fair bit about Bash

already. You can skip this section if you're only looking for the basics,

but remember it and refer back if you proceed much farther.

Variables in Bash are assigned much as they are in any programming

language:

testvar=5

foo=zen

bar="bash prompt"

Quotes are only needed in an assignment if a space (or special character,

discussed shortly) is a part of the variable.

Variables are referenced slightly differently than they are assigned:

> echo $testvar

5

> echo $foo

zen

> echo ${bar}

bash prompt

> echo $NotAssigned

>

A variable can be referred to as $bar or

${bar}. The braces are useful when it is unclear what

is being referenced: if I write $barley do I mean

${bar}ley or ${barley}? Note also

that referencing a value that hasn't been assigned doesn't generate an

error, instead returning nothing.

If you wish to include a special character in a variable, you will have to

quote it differently:

> newvar=$testvar

> echo $newvar

5

> newvar="$testvar"

> echo $newvar

5

> newvar='$testvar'

> echo $newvar

$testvar

> newvar=\$testvar

> echo $newvar

$testvar

>

The dollar sign isn't the only character that's special to the Bash shell,

but it's a simple example. An interesting step we can take to make use of

assigning a variable name to another variable name is to use

eval to dereference the stored variable name:

> echo $testvar

5

> echo $newvar

$testvar

> eval echo $newvar

5

>

Normally, the shell does only one round of substitutions on the expression

it is evaluating: if you say echo $newvar the shell

will only go so far as to determine that $newvar is

equal to the text string $testvar, it won't evaluate

what $testvar is equal to. eval

forces that evaluation.

In almost all cases in this document, I use the $(<command>)

convention for command substitution: that is,

$(date +%H%M)

means "substitute the output from the date +%H%M

command here." This works in Bash 2.0+. In some older versions of Bash,

prior to 1.14.7, you may need to use backquotes (`date

+%H%M`). Backquotes can be used in Bash 2.0+, but are being

phased out in favor of $(), which nests better. If you're using an earlier

version of Bash, you can usually substitute backquotes where you see $().

If the command substitution is escaped (ie. \$(command) ), then use

backslashes to escape BOTH your backquotes (ie. \'command\' ).

Many of the changes that can be made to Bash prompts that are discussed in

this HOWTO use non-printing characters. Changing the colour of the prompt

text, changing an Xterm title bar, and moving the cursor position all

require non-printing characters.

If I want a very simple prompt consisting of a greater-than sign and a

space:

[giles@nikola giles]$ PS1='> '

>

This is just a two character prompt. If I modify it so that it's a

bright yellow greater-than sign (colours are discussed in their own

section):

> PS1='\033[1;33m>\033[0m '

>

This works fine - until you type in a large command line. Because the

prompt still only consists of two printing characters (a greater-than sign

and a space) but the shell thinks that this prompt is eleven characters

long (I think it counts '\033' , '[1' and '[0' as one character each). You

can see this by typing a really long command line - you will find that the

shell wraps the text before it gets to the edge of the terminal, and in

most cases wraps it badly. This is because it's confused about the actual

length of the prompt.

So use this instead:

> PS1='\[\033[1;33m\]>\[\033[0m\] '

This is more complex, but it works. Command lines wrap properly. What's

been done is to enclose the '\033[1;33m' that starts the yellow colour in

'\[' and '\]' which tells the shell "everything between these escaped

square brackets, including the brackets themselves, is a non-printing

character." The same is done with the '\033[0m' that ends the colour.

When a file is sourced (by typing either source

filename or . filename at the command

line), the lines of code in the file are executed as if they were printed

at the command line. This is particularly useful with complex prompts, to

allow them to be stored in files and called up by sourcing the file they

are in.

In examples, you will find that I often include

#!/bin/bash at the beginning of files including

functions. This is not necessary if you are sourcing

a file, just as it isn't necessary to chmod +x a

file that is going to be sourced. I do this because it makes Vim (my

editor of choice, no flames please - you use what you like) think I'm

editing a shell script and turn on colour syntax highlighting.

As mentioned earlier, PS1, PS2, PS3, PS4, and PROMPT_COMMAND are all stored

in the Bash environment. For those of us coming from a DOS background, the

idea of tossing big hunks of code into the environment is horrifying,

because that DOS environment was small, and didn't exactly grow well.

There are probably practical limits to what you can and should put in the

environment, but I don't know what they are, and we're probably talking a

couple of orders of magnitude larger than what DOS users are used to. As

Dan put it:

"In my interactive shell I have 62 aliases and 25 functions. My rule

of thumb is that if I need something solely for interactive use and

can handily write it in bash I make it a shell function (assuming

it can't be easily expressed as an alias). If these people are

worried about memory they don't need to be using bash. Bash is one

of the largest programs I run on my linux box (outside of Oracle).

Run top sometime and press 'M' to sort by memory - see how close

bash is to the top of the list. Heck, it's bigger than sendmail!

Tell 'em to go get ash or something."

I guess he was using console only the day he tried that: running X and X

apps, I have a lot of stuff larger than Bash. But the idea is the same:

the environment is something to be used, and don't worry about overfilling

it.

I risk censure by Unix gurus when I say this (for the crime of

over-simplification), but functions are basically small shell scripts that

are loaded into the environment for the purpose of efficiency. Quoting Dan

again: “Shell functions are about as efficient as they can be. It is the

approximate equivalent of sourcing a bash/bourne shell script save that no

file I/O need be done as the function is already in memory. The shell

functions are typically loaded from [.bashrc or .bash_profile] depending on

whether you want them only in the initial shell or in subshells as well.

Contrast this with running a shell script: Your shell forks, the child does

an exec, potentially the path is searched, the kernel opens the file and

examines enough bytes to determine how to run the file, in the case of a

shell script a shell must be started with the name of the script as its

argument, the shell then opens the file, reads it and executes the

statements. Compared to a shell function, everything other than executing

the statements can be considered unnecessary overhead.”

Aliases are simple to create:

alias d="ls --color=tty --classify"

alias v="d --format=long"

alias rm="rm -i"

Any arguments you pass to the alias are passed to the command line of the

aliased command (ls in the first two cases). Note that aliases can be

nested, and they can be used to make a normal unix command behave in a

different way. (I agree with the argument that you shouldn't use the

latter kind of aliases - if you get in the habit of relying on "rm *" to

ask you if you're sure, you may lose important files on a system that

doesn't use your alias.)

Functions are used for more complex program structures. As a general rule,

use an alias for anything that can be done in one line. Functions differ

from shell scripts in that they are loaded into the environment so that

they work more quickly. As a general rule again, you would want to

keep functions relatively small, and any shell script that gets relatively

large should remain a shell script rather than turning it into a function.

Your decision to load something as a function is also going to depend on

how often you use it. If you use a small shell script infrequently, leave

it as a shell script. If you use it often, turn it into a function.

To modify the behaviour of ls, you could do

something like the following:

function lf

{

ls --color=tty --classify $*

echo "$(ls -l $* | wc -l) files"

}

This could readily be set as an alias, but for the sake of example, we'll

make it a function. If you type the text shown into a text file and then

source that file, the function will be in your environment, and be

immediately available at the command line without the overhead of a shell

script mentioned previously. The usefulness of this becomes more obvious

if you consider adding more functionality to the above function, such as

using an if statement to execute some special code when links are found in

the listing.

Bash provides an environment variable called PROMPT_COMMAND.

The contents of this variable are executed as a regular Bash command just

before Bash displays a prompt.

[21:55:01][giles@nikola:~] PS1="[\u@\h:\w]\$ "

[giles@nikola:~] PROMPT_COMMAND="date +%H%M"

2155

[giles@nikola:~] d

bin mail

2156

[giles@nikola:~]

What happened above was that I changed PS1 to no longer include the

\t escape sequence (added in a previous section), so

the time was no longer a part of the prompt. Then I used date

+%H%M to display the time in a format I like better. But it

appears on a different line than the prompt. Tidying this up using

echo -n ... as shown below works with Bash 2.0+, but

appears not to work with Bash 1.14.7: apparently the prompt is drawn in a

different way, and the following method results in overlapping text.

2156

[giles@nikola:~] PROMPT_COMMAND="echo -n [$(date +%H%M)]"

[2156][giles@nikola:~]$

[2156][giles@nikola:~]$ d

bin mail

[2157][giles@nikola:~]$ unset PROMPT_COMMAND

[giles@nikola:~]

echo -n ... controls the output of the

date command and suppresses the trailing newline,

allowing the prompt to appear all on one line. At the end, I used the

unset command to remove the

PROMPT_COMMAND environment variable.

You can use the output of regular Linux commands directly in the prompt as

well. Obviously, you don't want to insert a lot of material, or it will

create a large prompt. You also want to use a fast

command, because it's going to be executed every time your prompt appears

on the screen, and delays in the appearance of your prompt while you're

working can be very annoying. (Unlike the previous example that this

closely resembles, this does work with Bash 1.14.7.)

[21:58:33][giles@nikola:~]$ PS1="[\$(date +%H%M)][\u@\h:\w]\$ "

[2159][giles@nikola:~]$ ls

bin mail

[2200][giles@nikola:~]$

It's important to notice the backslash before the dollar sign of the

command substitution. Without it, the external command is executed exactly

once: when the PS1 string is read into the environment. For this prompt,

that would mean that it would display the same time no matter how long the

prompt was used. The backslash protects the contents of $() from immediate

shell interpretation, so date is called every time

a prompt is generated.

Linux comes with a lot of small utility programs like

date, grep, or wc

that allow you to manipulate data. If you find yourself trying to create

complex combinations of these programs within a prompt, it may be easier to

make an alias, function, or shell script of your own, and call it from the

prompt. Escape sequences are often required in bash shell scripts to

ensure that shell variables are expanded at the correct time (as seen above

with the date command): this is raised to another level within the prompt

PS1 line, and avoiding it by creating functions is a good idea.

An example of a small shell script used within a prompt is given below:

#!/bin/bash

# lsbytesum - sum the number of bytes in a directory listing

TotalBytes=0

for Bytes in $(ls -l | grep "^-" | awk '{ print $5 }')

do

let TotalBytes=$TotalBytes+$Bytes

done

TotalMeg=$(echo -e "scale=3 \n$TotalBytes/1048576 \nquit" | bc)

echo -n "$TotalMeg"

I used to keep this as a function, it now lives as a shell script in my

~/bin directory, which is on my path.

Used in a prompt:

[2158][giles@nikola:~]$ PS1="[\u@\h:\w (\$(lsbytesum) Mb)]\$ "

[giles@nikola:~ (0 Mb)]$ cd /bin

[giles@nikola:/bin (4.498 Mb)]$

You'll find I put username, machine name, time, and current directory name

in most of my prompts. With the exception of the time, these are very

standard items to find in a prompt, and time is probably the next most

common addition. But what you include is entirely a matter of personal

taste. Here is an interesting example to help give you ideas.

Dan's prompt is minimal but very effective, particularly for the way he

works.

[giles@nikola:~]$ PS1="\!,\l,\$?\$ "

1095,4,0$ non-command

bash: non-command: command not found

1096,4,127$

Dan doesn't like that having the current working directory can resize the

prompt drastically as you move through the directory tree, so he keeps

track of that in his head (or types "pwd"). He learned Unix with csh and

tcsh, so he uses his command history extensively (something many of us

weaned on Bash do not do), so the first item in the prompt is the history

number. The second item is the tty number, an item that can be useful to

"screen" users. The third item is the exit value of the last

command/pipeline (note that this is rendered useless by any command

executed within the prompt - you can work around that by capturing it to

a variable and playing it back, though). Finally, the "\$" is a dollar

sign for a regular user, and switches to a hash mark ("#") if the user is

root.

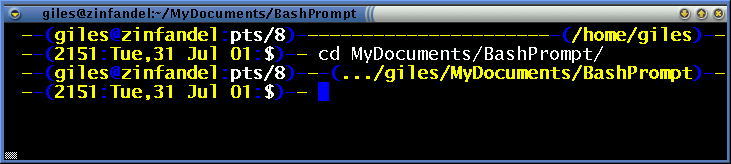

As the prompts you use become more complex, it becomes more and more

cumbersome to type them in at the prompt, and more practical to make them

into some sort of text file. I have adopted the method used by the

Bashprompt package (discussed later in this document: Chapter 8, The Bash Prompt Package), which is to put the primary commands

for the prompt in one file with the PS1 string in particular defined within

a function of the same name as the file itself. It's not the only way to

do it, but it works well. Take the following example:

#!/bin/bash

function tonka {

# Named "Tonka" because of the colour scheme

local WHITE="\[\033[1;37m\]"

local LIGHT_BLUE="\[\033[1;34m\]"

local YELLOW="\[\033[1;33m\]"

local NO_COLOUR="\[\033[0m\]"

case $TERM in

xterm*|rxvt*)

TITLEBAR='\[\033]0;\u@\h:\w\007\]'

;;

*)

TITLEBAR=""

;;

esac

PS1="$TITLEBAR\

$YELLOW-$LIGHT_BLUE-(\

$YELLOW\u$LIGHT_BLUE@$YELLOW\h\

$LIGHT_BLUE)-(\

$YELLOW\$PWD\

$LIGHT_BLUE)-$YELLOW-\

\n\

$YELLOW-$LIGHT_BLUE-(\

$YELLOW\$(date +%H%M)$LIGHT_BLUE:$YELLOW\$(date \"+%a,%d %b %y\")\

$LIGHT_BLUE:$WHITE\\$ $LIGHT_BLUE)-$YELLOW-$NO_COLOUR "

PS2="$LIGHT_BLUE-$YELLOW-$YELLOW-$NO_COLOUR "

}

You can work with it as follows:

[giles@nikola:/bin (4.498 Mb)]$ cd

[giles@nikola:~ (0 Mb)]$ vim tonka

...

[giles@nikola:~ (0 Mb)]$ source tonka

[giles@nikola:~ (0 Mb)]$ tonka

[giles@nikola:~ (0 Mb)]$ unset tonka

Table of Contents

As mentioned before, non-printing escape sequences have to be enclosed in

\[\033[ and \]. For colour

escape sequences, they should also be followed by a lowercase

m.

If you try out the following prompts in an xterm and find that you aren't

seeing the colours named, check out your

~/.Xdefaults file (and

possibly its bretheren) for lines like

XTerm*Foreground: BlanchedAlmond.

This can be commented out by placing an exclamation mark ("!") in front of

it. Of course, this will also be dependent on what terminal emulator

you're using. This is the likeliest place that your term foreground

colours would be overridden.

To include blue text in the prompt:

PS1="\[\033[34m\][\$(date +%H%M)][\u@\h:\w]$ "

The problem with this prompt is that the blue colour that starts with the

34 colour code is never switched back to the regular colour, so any text

you type after the prompt is still in the colour of the prompt. This is

also a dark shade of blue, so combining it with the

bold code might help:

PS1="\[\033[1;34m\][\$(date +%H%M)][\u@\h:\w]$\[\033[0m\] "

The prompt is now in light blue, and it ends by switching the colour

back to nothing (whatever foreground colour you had previously).

Here are the rest of the colour equivalences:

Black 0;30 Dark Gray 1;30

Blue 0;34 Light Blue 1;34

Green 0;32 Light Green 1;32

Cyan 0;36 Light Cyan 1;36

Red 0;31 Light Red 1;31

Purple 0;35 Light Purple 1;35

Brown 0;33 Yellow 1;33

Light Gray 0;37 White 1;37

Daniel Dui (ddui@iee.org) points out that to be strictly accurate, we must

mention that the list above is for colours at the console. In an xterm,

the code 1;31 isn't "Light Red," but "Bold Red."

This is true of all the colours.

You can also set background colours by using 44 for Blue background, 41 for

a Red background, etc. There are no bold background colours. Combinations

can be used, like Light Red text on a Blue background:

\[\033[44;1;31m\], although setting the colours

separately seems to work better (ie.

\[\033[44m\]\[\033[1;31m\]). Other codes

available include 4: Underscore, 5: Blink, 7: Inverse, and 8: Concealed.

Note

Many people (myself included) object strongly to the

"blink" attribute because it's extremely distracting and irritating.

Fortunately, it doesn't work in any terminal emulators

that I'm aware of - but it will still work on the console.

Note

If you were wondering (as I did) "What use is a 'Concealed' attribute?!" -

I saw it used in an example shell script (not a prompt) to allow someone to

type in a password without it being echoed to the screen. However, this

attribute doesn't seem to be honoured by many terms other than "Xterm."

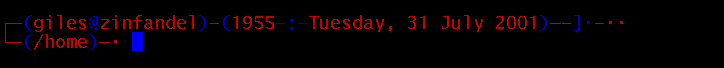

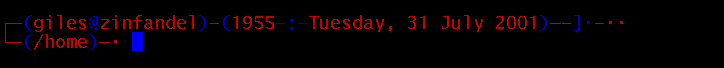

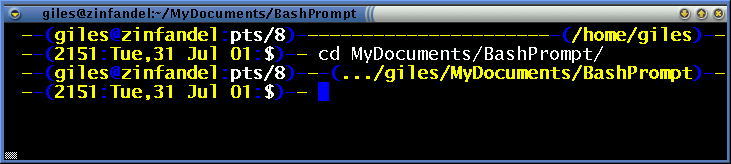

Based on a prompt called "elite2" in the Bashprompt package (which I

have modified to work better on a standard console, rather than with the

special xterm fonts required to view the original properly), this is a

prompt I've used a lot:

function elite

{

local GRAY="\[\033[1;30m\]"

local LIGHT_GRAY="\[\033[0;37m\]"

local CYAN="\[\033[0;36m\]"

local LIGHT_CYAN="\[\033[1;36m\]"

local NO_COLOUR="\[\033[0m\]"

case $TERM in

xterm*|rxvt*)

local TITLEBAR='\[\033]0;\u@\h:\w\007\]'

;;

*)

local TITLEBAR=""

;;

esac

local temp=$(tty)

local GRAD1=${temp:5}

PS1="$TITLEBAR\

$GRAY-$CYAN-$LIGHT_CYAN(\

$CYAN\u$GRAY@$CYAN\h\

$LIGHT_CYAN)$CYAN-$LIGHT_CYAN(\

$CYAN\#$GRAY/$CYAN$GRAD1\

$LIGHT_CYAN)$CYAN-$LIGHT_CYAN(\

$CYAN\$(date +%H%M)$GRAY/$CYAN\$(date +%d-%b-%y)\

$LIGHT_CYAN)$CYAN-$GRAY-\

$LIGHT_GRAY\n\

$GRAY-$CYAN-$LIGHT_CYAN(\

$CYAN\$$GRAY:$CYAN\w\

$LIGHT_CYAN)$CYAN-$GRAY-$LIGHT_GRAY "

PS2="$LIGHT_CYAN-$CYAN-$GRAY-$NO_COLOUR "

}

I define the colours as temporary shell variables in the name of

readability. It's easier to work with. The "GRAD1" variable is a check to

determine what terminal you're on. Like the test to determine if you're

working in an Xterm, it only needs to be done once. The prompt you see

look like this, except in colour:

--(giles@gcsu202014)-(30/pts/6)-(0816/01-Aug-01)--

--($:~/tmp)--

To help myself remember what colours are available, I wrote a script that

output all the colours to the screen. Daniel Crisman has supplied a much

nicer version which I include below:

#!/bin/bash

#

# This file echoes a bunch of color codes to the

# terminal to demonstrate what's available. Each

# line is the color code of one forground color,

# out of 17 (default + 16 escapes), followed by a

# test use of that color on all nine background

# colors (default + 8 escapes).

#

T='gYw' # The test text

echo -e "\n 40m 41m 42m 43m\

44m 45m 46m 47m";

for FGs in ' m' ' 1m' ' 30m' '1;30m' ' 31m' '1;31m' ' 32m' \

'1;32m' ' 33m' '1;33m' ' 34m' '1;34m' ' 35m' '1;35m' \

' 36m' '1;36m' ' 37m' '1;37m';

do FG=${FGs// /}

echo -en " $FGs \033[$FG $T "

for BG in 40m 41m 42m 43m 44m 45m 46m 47m;

do echo -en "$EINS \033[$FG\033[$BG $T \033[0m";

done

echo;

done

echo

ANSI escape sequences allow you to move the cursor around the screen at

will. This is more useful for full screen user interfaces generated by

shell scripts, but can also be used in prompts. The movement escape

sequences are as follows:

- Position the Cursor:

\033[<L>;<C>H

Or

\033[<L>;<C>f

puts the cursor at line L and column C.

- Move the cursor up N lines:

\033[<N>A

- Move the cursor down N lines:

\033[<N>B

- Move the cursor forward N columns:

\033[<N>C

- Move the cursor backward N columns:

\033[<N>D

- Clear the screen, move to (0,0):

\033[2J

- Erase to end of line:

\033[K

- Save cursor position:

\033[s

- Restore cursor position:

\033[u

The latter two codes are NOT honoured by many terminal emulators. The only

ones that I'm aware of that do are xterm and nxterm - even though the

majority of terminal emulators are based on xterm code. As far as I can

tell, rxvt, kvt, xiterm, and Eterm do not support them. They are supported

on the console.

Try putting in the following line of code at the prompt (it's a little

clearer what it does if the prompt is several lines down the terminal when

you put this in):

echo -en "\033[7A\033[1;35m BASH \033[7B\033[6D"

This should move the cursor seven lines up screen, print the word

" BASH ", and then return to where it

started to produce a normal prompt. This isn't a prompt: it's just a

demonstration of moving the cursor on screen, using colour to emphasize

what has been done.

Save this in a file called "clock":

#!/bin/bash

function prompt_command {

let prompt_x=$COLUMNS-5

}

PROMPT_COMMAND=prompt_command

function clock {

local BLUE="\[\033[0;34m\]"

local RED="\[\033[0;31m\]"

local LIGHT_RED="\[\033[1;31m\]"

local WHITE="\[\033[1;37m\]"

local NO_COLOUR="\[\033[0m\]"

case $TERM in

xterm*)

TITLEBAR='\[\033]0;\u@\h:\w\007\]'

;;

*)

TITLEBAR=""

;;

esac

PS1="${TITLEBAR}\

\[\033[s\033[1;\$(echo -n \${prompt_x})H\]\

$BLUE[$LIGHT_RED\$(date +%H%M)$BLUE]\[\033[u\033[1A\]

$BLUE[$LIGHT_RED\u@\h:\w$BLUE]\

$WHITE\$$NO_COLOUR "

PS2='> '

PS4='+ '

}

This prompt is fairly plain, except that it keeps a 24 hour clock in the

upper right corner of the terminal (even if the terminal is resized). This

will NOT work on the terminal emulators that I mentioned that don't accept

the save and restore cursor position codes. If you try to run this prompt

in any of those terminal emulators, the clock will appear correctly, but

the prompt will be trapped on the second line of the terminal.

See also the section called "The Elegant Useless Clock Prompt" for a

more extensive use of these codes.

I'm not sure that these escape sequences strictly qualify as "ANSI Escape

Sequences," but in practice their use is almost identical so I've included

them in this chapter.

Non-printing escape sequences can be used to produce interesting effects in

prompts. To use these escape sequences, you need to enclose them in

\[ and \] (as discussed in

the section called "Non-Printing Characters in Prompts", telling Bash to ignore this material

while calculating the size of the prompt. Failing to include these

delimiters results in line editing code placing the cursor incorrectly

because it doesn't know the actual size of the prompt. Escape sequences

must also be preceded by \033[ in Bash prior to

version 2, or by either \033[ or

\e[ in later versions.

If you try to change the title bar of your Xterm with your prompt

when you're at the console, you'll produce garbage in your prompt.

To avoid this, test the TERM environment variable to tell if your prompt

is going to be in an Xterm.

function proml

{

case $TERM in

xterm*)

local TITLEBAR='\[\033]0;\u@\h:\w\007\]'

;;

*)

local TITLEBAR=''

;;

esac

PS1="${TITLEBAR}\

[\$(date +%H%M)]\

[\u@\h:\w]\

\$ "

PS2='> '

PS4='+ '

}

This is a function that can be incorporated into

~/.bashrc. The

function name could then be called to execute the function. The function,

like the PS1 string, is stored in the environment. Once the PS1 string is

set by the function, you can remove the function from the environment with

unset proml. Since the prompt can't

change from being in an Xterm

to being at the console, the TERM variable isn't tested every time the

prompt is generated. I used continuation markers (backslashes) in the

definition of the prompt, to allow it to be continued on multiple lines.

This improves readability, making it easier to modify and debug.

The first step in creating this prompt is to test if the shell we're

starting is an xterm or not: if it is, the shell variable (${TITLEBAR}) is

defined. It consists of the appropriate escape sequences, and

\u@\h:\w, which puts

<user>@<machine>:<working directory> in the Xterm title

bar. This is particularly useful with minimized Xterms, making them more

rapidly identifiable. The other material in this prompt should be familiar

from previous prompts we've created.

The only drawback to manipulating the Xterm title bar like this occurs

when you log into a system on which you haven't set up the title bar hack:

the Xterm will continue to show the information from the previous system

that had the title bar hack in place.

A suggestion from Charles Lepple (<clepple at negativezero dot

org>) on setting the window title of the Xterm and the title of the

corresponding icon separately. He uses this under WindowMaker because the

title that's appropriate for an Xterm is usually too long for a 64x64 icon.

"\[\e]1;icon-title\007\e]2;main-title\007\]". He says to set this in the

prompt command because “I tried putting the string in PS1, but it

causes flickering under some window managers because it results in setting

the prompt multiple times when you are editing a multi-line command (at

least under bash 1.4.x -- and I was too lazy to fully explore the reasons

behind it).” I had no trouble with it in the PS1 string, but didn't

use any multi-line commands. He also points out that it works under xterm,

xwsh, and dtterm, but not gnome-terminal (which uses only the main title).

I also found it to work with rxvt, but not kterm.

Non-screen users should skip this section. Of course, screen is an awesome

program and what you should really do is rush out and find out what screen

is - if you've read this far in the HOWTO, you're enough of a Command Line

Interface Junkie that you need to know.

If you use screen in Xterms and you want to manipulate the title bar, your

life may just have become a bit more complicated ... Screen can, but doesn't

automatically, treat the Xterm title bar as a hardstatus line (whatever

that means, but it's where we put our Xterm title). If you're a RedHat

user, you'll probably find the following line in your

~/.screenrc:

termcapinfo xterm 'hs:ts=\E]2;:fs=\007:ds=\E]2;screen\007'

If that line isn't in there, you should put it in. This allows the

titlebar manipulations in the previous section to work under Xterm. But I

found they failed when I used rxvt. I e-mailed a question about this to

the screen maintainers, and Michael Schroeder (one of those good people

labouring behind the scenes to make free Unix/Linux software as great as it

is) told me to add the following to my ~/.screenrc:

termcapinfo rxvt 'hs:ts=\E]2;:fs=\007:ds=\E]2;screen\007'

I don't know if this will work for other Xterm variants, but since the two

lines are functionally identical except for the name of the Xterm type,

perhaps ... I leave this as an exercise for the reader. It did fix my

problem, although I haven't researched further to see if it interferes with

the icon-titlebar naming distinction.

As with so many things in Unix, there is more than one way to achieve the

same ends. A utility called tput can also be used to

move the cursor around the screen, get back information about the status of the

terminal, or set colours. man tput doesn't go into much

detail about the available commands, but Emilio Lopes e-mailed me to point

out that man terminfo will give you a

huge list of capabilities, many of which are device

independent, and therefore better than the escape sequences previously

mentioned. He suggested that I rewrite all the examples using

tput for this reason. He is correct that I should, but

I've had some trouble controlling it and getting it to do everything I want

it to. However, I did rewrite one prompt which you can see as an example:

the section called "The Floating Clock Prompt".

Here is a list of tput capabilities that I have found useful:

tput Colour Capabilities

- tput setab [1-7]

Set a background colour using ANSI escape

- tput setb [1-7]

Set a background colour

- tput setaf [1-7]

Set a foreground colour using ANSI escape

- tput setf [1-7]

Set a foreground colour

tput Text Mode Capabilities

- tput bold

Set bold mode

- tput dim

turn on half-bright mode

- tput smul

begin underline mode

- tput rmul

exit underline mode

- tput rev

Turn on reverse mode

- tput smso

Enter standout mode (bold on rxvt)

- tput rmso

Exit standout mode

- tput sgr0

Turn off all attributes (doesn't work quite as expected)

tput Cursor Movement Capabilities

- tput cup Y X

Move cursor to screen location X,Y (top left is 0,0)

- tput sc

Save the cursor position

- tput rc

Restore the cursor position

- tput lines

Output the number of lines of the terminal

- tput cols

Output the number of columns of the terminal

- tput cub N

Move N characters left

- tput cuf N

Move N characters right

- tput cub1

move left one space

- tput cuf1

non-destructive space (move right one space)

- tput ll

last line, first column (if no cup)

- tput cuu1

up one line

tput Clear and Insert Capabilities

- tput ech N

Erase N characters

- tput clear

clear screen and home cursor

- tput el1

Clear to beginning of line

- tput el

clear to end of line

- tput ed

clear to end of screen

- tput ich N

insert N characters (moves rest of line forward!)

- tput il N

insert N lines

This is by no means a complete list of what terminfo and

tput allow, in fact it's only the beginning.

man tput and man terminfo if you want

to know more.

Outside of the characters that you can type on your keyboard, there are a

lot of other characters you can print on your screen. I've created a

script to allow you to check out what the font you're using has available

for you. The main command you need to use to utilize these characters is

"echo -e". The "-e" switch tells echo to enable interpretation of

backslash-escaped characters. What you see when you look at octal 200-400

will be very different with a VGA font from what you will see with a

standard Linux font. Be warned that some of these escape sequences have

odd effects on your terminal, and I haven't tried to prevent them from

doing whatever they do. The linedraw and block characters that are used

heavily by the Bashprompt project are between octal 260 and 337 in the VGA

fonts.

#!/bin/bash

# Script: escgen

function usage {

echo -e "\033[1;34mescgen\033[0m <lower_octal_value> [<higher_octal_value>]"

echo " Octal escape sequence generator: print all octal escape sequences"

echo " between the lower value and the upper value. If a second value"

echo " isn't supplied, print eight characters."

echo " 1998 - Giles Orr, no warranty."

exit 1

}

if [ "$#" -eq "0" ]

then

echo -e "\033[1;31mPlease supply one or two values.\033[0m"

usage

fi

let lower_val=${1}

if [ "$#" -eq "1" ]

then

# If they don't supply a closing value, give them eight characters.

upper_val=$(echo -e "obase=8 \n ibase=8 \n $lower_val+10 \n quit" | bc)

else

let upper_val=${2}

fi

if [ "$#" -gt "2" ]

then

echo -e "\033[1;31mPlease supply two values.\033[0m"

echo

usage

fi

if [ "${lower_val}" -gt "${upper_val}" ]

then

echo -e "\033[1;31m${lower_val} is larger than ${upper_val}."

echo

usage

fi

if [ "${upper_val}" -gt "777" ]

then

echo -e "\033[1;31mValues cannot exceed 777.\033[0m"

echo

usage

fi

let i=$lower_val

let line_count=1

let limit=$upper_val

while [ "$i" -lt "$limit" ]

do

octal_escape="\\$i"

echo -en "$i:'$octal_escape' "

if [ "$line_count" -gt "7" ]

then

echo

# Put a hard return in.

let line_count=0

fi

let i=$(echo -e "obase=8 \n ibase=8 \n $i+1 \n quit" | bc)

let line_count=$line_count+1

done

echo

You can also use xfd to display all the characters in

an X font, with the command xfd -fn <fontname>.

Clicking on any given

character will give you lots of information about that character, including

its octal value. The script given above will be useful on the console, and

if you aren't sure of the current font name.

Table of Contents

The Bash Prompt package was available at http://bash.current.nu/, and is the

work of several people, co-ordinated by Rob Current (aka BadLandZ). The

site was down in July 2001, but Rob Current assures me it will be back up

soon. The package is in beta, but offers a simple way of using multiple

prompts (or themes), allowing you to set prompts for login shells, and for

subshells (ie. putting PS1 strings in ~/.bash_profile

and ~/.bashrc). Most of the themes use the extended

VGA character set, so they look bad unless they're used with VGA fonts

(which aren't the default on most systems). Little work has been done on

this project recently: I hope there's some more progress.

To use some of the most attractive prompts in the Bash Prompt package, you

need to get and install fonts that support the character sets expected by

the prompts. These are "VGA Fonts," which support different character sets

than regular Xterm fonts. Standard Xterm fonts support an extended

alphabet, including a lot of letters with accents. In VGA fonts, this

material is replaced by graphical characters - blocks, dots, lines. I

asked for an explanation of this difference, and SĂ©rgio Vale e Pace

(space@gold.com.br) wrote me:

I love computer history so here goes:

When IBM designed the first PC they needed some character codes to use, so

they got the ASCII character table (128 numbers, letters, and some

punctuation) and to fill a byte addressed table they added 128 more

characters. Since the PC was designed to be a home computer, they fill the

remaining 128 characters with dots, lines, points, etc, to be able to do

borders, and grayscale effects (remember that we are talking about 2 color

graphics).

Time passes, PCs become a standard, IBM creates more powerful systems and

the VGA standard is born, along with 256 colour graphics, and IBM continues

to include their IBM-ASCII characters table.

More time passes, IBM has lost their leadership in the PC market, and the

OS authors dicover that there are other languages in the world that use

non-english characters, so they add international alphabet support in their

systems. Since we now have bright and colorful screens, we can trash the

dots, lines, etc. and use their space for accented characters and some

greek letters, which you'll see in Linux.

Getting and installing these fonts is a somewhat involved process. First,

retrieve the font(s). Next, ensure they're .pcf or .pcf.gz files. If

they're .bdf files, investigate the "bdftopcf" command (ie. read the man

page). Drop the .pcf or .pcf.gz files into the

dir (this is the correct directory for RedHat

5.1 through 7.1, it may be different on other distributions).

cd to that directory, and run mkfontdir.

Then run xset fp rehash and/or restart your X font

server, whichever

applies to your situation. Sometimes it's a good idea to go into the

fonts.alias file in the same directory, and

create shorter alias names for the fonts.

To use the new fonts, you start your Xterm program of choice with the

appropriate command to your Xterm, which can be found either in the man

page or by using the "--help" parameter on the command line. Popular terms

would be used as follows:

xterm -font <fontname>

OR

xterm -fn <fontname> -fb <fontname-bold>

Eterm -F <fontname>

rxvt -fn <fontname>

VGA fonts are available from Stumpy's ANSI Fonts

page at

http://home.earthlink.net/~us5zahns/enl/ansifont.html (which I have

borrowed from extensively while writing this).

Xterm and rxvt can be switched into line-draw mode on the fly with the

appropriate escape sequence. You'll need to switch back after you've

output the characters you wanted or any text following it will be garbled.

Prompts based on these output codes don't work on the console, instead

producing the text equivalents.

To start a sequence of line draw characters, use an echo

-e and the \033(0 escape sequence. Most of

the characters worth using are in the range lower case "a" through "z".

Terminate the string with another escape sequence,

\033(B .

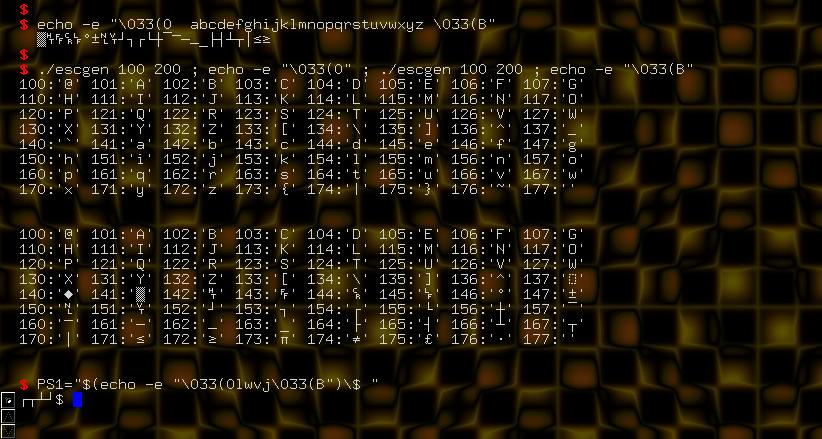

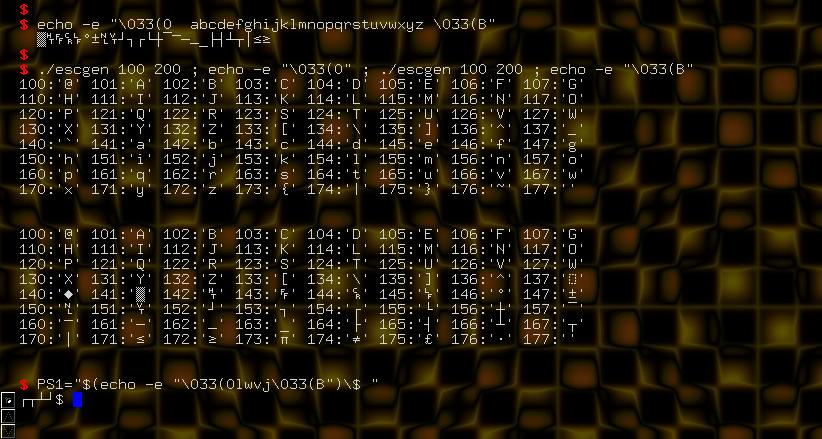

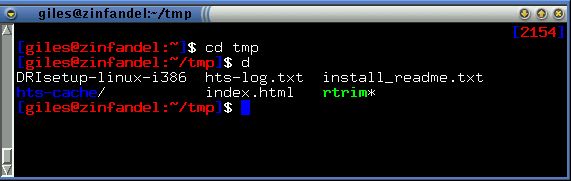

The best method I've found for testing this is shown in the image below:

use the escgen script mentioned earlier in the HOWTO to

show the 100 to 200 octal range, echo the first escape

sequence, run the escgen script for the same range, and

echo the closing escape sequence. The image also shows

how to use this in a prompt.

Using escape sequences in RXVT (also works in Xterm and RXVT derivatives

like aterm, which is used here) to produce line draw characters. The

"escgen" script used above is given earlier in the HOWTO.

Table of Contents

The explanations in this HOWTO have shown how to make PS1 environment

variables, or how to incorporate those PS1 and PS2 strings into functions

that could be called by ~/.bashrc or as a theme by the bashprompt

package.

Using the bashprompt package, you would type bashprompt

-i to see a list of available themes. To set the prompt in

future login shells (primarily the console, but also telnet and Xterms,

depending on how your Xterms are set up), you would type

bashprompt -l themename.

bashprompt then modifies your

~/.bash_profile to call the requested theme when

it starts. To set the prompt in future subshells (usually Xterms, rxvt,

etc.), you type bashprompt -s themename, and

bashprompt modifies your ~/.bashrc file to call

the appropriate theme at startup.

See also the section called "Setting the PS Strings Permanently". for

Johan Kullstam's note regarding the importance of putting the PS?

strings in ~/.bashrc .

You can change the prompt in your current terminal (using the example

"elite" function above) by typing source elite

followed by elite (assuming that the elite

function file is the working directory). This is somewhat cumbersome, and

leaves you with an extra function (elite) in your environment space - if

you want to clean up the environment, you would have to type

unset elite as well. This would seem like an

ideal candidate for a small shell script, but a script doesn't work here

because the script cannot change the environment of your current shell: it

can only change the environment of the subshell it runs in. As soon as the

script stops, the subshell goes away, and the changes the script made to

the environment are gone. What can change environment

variables of your current shell are environment functions. The bashprompt

package puts a function called callbashprompt into your

environment, and, while they don't document it, it can be called to load

any bashprompt theme on the fly. It looks in the theme directory it

installed (the theme you're calling has to be there), sources the function

you asked for, loads the function, and then unsets the function, thus

keeping your environment uncluttered. callbashprompt

wasn't intended to be used this way, and has no error checking, but if you

keep that in mind, it works quite well.

If you have a specific prompt to go with a particular project, or some

reason to load different prompts at different times, you can use multiple

bashrc files instead of always using your ~/.bashrc

file. The Bash command is something like bash --rcfile

/home/giles/.bashprompt/bashrc/bashrcdan, which will start a

new version of Bash in your current terminal. To use this in combination

with a Window Manager menuing system, use a command like rxvt -e

bash --rcfile /home/giles/.bashprompt/bashrc/bashrcdan. The

exact command you use will be dependent on the syntax of your X term of

choice and the location of the bashrc file you're using.

Table of Contents

This is a "proof of concept" more than an attractive prompt: changing

colours within the prompt dynamically. In this example, the colour of the

host name changes depending on the load (as a warning).

#!/bin/bash

# "hostloadcolour" - 17 October 98, by Giles

#

# The idea here is to change the colour of the host name in the prompt,

# depending on a threshold load value.

# THRESHOLD_LOAD is the value of the one minute load (multiplied

# by one hundred) at which you want

# the prompt to change from COLOUR_LOW to COLOUR_HIGH

THRESHOLD_LOAD=200

COLOUR_LOW='1;34'

# light blue

COLOUR_HIGH='1;31'

# light red

function prompt_command {

ONE=$(uptime | sed -e "s/.*load average: \(.*\...\), \(.*\...\), \(.*\...\)/\1/" -e "s/ //g")

# Apparently, "scale" in bc doesn't apply to multiplication, but does

# apply to division.

ONEHUNDRED=$(echo -e "scale=0 \n $ONE/0.01 \nquit \n" | bc)

if [ $ONEHUNDRED -gt $THRESHOLD_LOAD ]

then

HOST_COLOUR=$COLOUR_HIGH

# Light Red

else

HOST_COLOUR=$COLOUR_LOW

# Light Blue

fi

}

function hostloadcolour {

PROMPT_COMMAND=prompt_command

PS1="[$(date +%H%M)][\u@\[\033[\$(echo -n \$HOST_COLOUR)m\]\h\[\033[0m\]:\w]$ "

}

Using your favorite editor, save this to a file named "hostloadcolour". If

you have the Bashprompt package installed, this will work as a theme. If you

don't, type source hostloadcolour and then hostloadcolour.

Either way, "prompt_command" becomes a function in your environment.

If you examine the code, you will notice that the colours ($COLOUR_HIGH and

$COLOUR_LOW) are set using only a partial colour code, ie. "1;34" instead of

"\[\033[1;34m\]", which I would have preferred. I have been unable to get

it to work with the complete code. Please let me know if you manage this.

Table of Contents

- Built-in Escape Sequences

- Date and Time

- Counting Files in the Current Directory

- Total Bytes in the Current Directory

- Checking the Current TTY

- Stopped Jobs Count

- Load

- Uptime

- Number of Processes

- Controlling the Size and Appearance of $PWD

- Laptop Power

- Having the Prompt Ignored on Cut and Paste

- New Mail

- Prompt Beeps After Long-Running Commands

This section shows how to put various pieces of information into the Bash

prompt. There are an infinite number of things that could be put in your

prompt. Feel free to send me examples, I'll try to include what I think

will be most widely used. If you have an alternate way to retrieve a piece

of information here, and feel your method is more efficient, please contact

me. It's easy to write bad code, I do it often, but it's great to write

elegant code, and a pleasure to read it. I manage it every once in a

while, and would love to have more of it to put in here.

To incorporate shell code in prompts, it has to be escaped. Usually, this

will mean putting it inside \$(<command>) so

that the output of command is substituted each time

the prompt is generated.

Please keep in mind that I develop and test this code on a single user

900 MHz Athlon with 256 meg of RAM, so the delay generated by these code

snippets doesn't usually mean much to me. To help with this, I recently

assembled a 25 MHz 486 SX with 16 meg of RAM, and you will see the output

of the "time" command for each snippet to indicate how much of a delay it

causes on a slower machine.

See the section called "Bash Prompt Escape Sequences" for a complete

list of built-in escape sequences. This list is taken directly from the

Bash man page, so you can also look there.

If you don't like the built-ins for date and time, extracting the same

information from the date command is relatively

easy. Examples already seen in this HOWTO include

date +%H%M,

which will put in the hour in 24 hour format, and the minute.

date "+%A, %d %B %Y" will give something like

"Sunday, 06 June 1999". For a full list

of the interpreted sequences, type date --help or

man date.

Relative speed: "date ..." takes about 0.12 seconds on an unloaded 486SX25.

To determine how many files there are in the current directory, put in

ls -1 | wc -l. This uses wc

to do a count of the number of lines (-l) in the output of

ls -1. It doesn't count dotfiles. Please note that

ls -l (that's an "L" rather than a "1" as in the

previous examples) which I used in previous versions of this HOWTO will

actually give you a file count one greater than the actual count. Thanks

to Kam Nejad for this point.

If you want to count only files and NOT include symbolic links (just an

example of what else you could do), you could use ls -l | grep

-v ^l | wc -l (that's an "L" not a "1" this time, we want a

"long" listing here). grep checks for any line

beginning with "l" (indicating a link), and discards that line (-v).

Relative speed: "ls -1 /usr/bin/ | wc -l" takes about 1.03 seconds on an

unloaded 486SX25 (/usr/bin/ on this machine has 355 files). "ls -l

/usr/bin/ | grep -v ^l | wc -l" takes about 1.19 seconds.

If you want to know how much space the contents of the current directory

take up, you can use something like the following:

let TotalBytes=0

for Bytes in $(ls -l | grep "^-" | awk '{ print $5 }')

do

let TotalBytes=$TotalBytes+$Bytes

done

# The if...fi's give a more specific output in byte, kilobyte, megabyte,

# and gigabyte

if [ $TotalBytes -lt 1024 ]; then

TotalSize=$(echo -e "scale=3 \n$TotalBytes \nquit" | bc)

suffix="b"

elif [ $TotalBytes -lt 1048576 ]; then

TotalSize=$(echo -e "scale=3 \n$TotalBytes/1024 \nquit" | bc)

suffix="kb"

elif [ $TotalBytes -lt 1073741824 ]; then

TotalSize=$(echo -e "scale=3 \n$TotalBytes/1048576 \nquit" | bc)

suffix="Mb"

else

TotalSize=$(echo -e "scale=3 \n$TotalBytes/1073741824 \nquit" | bc)

suffix="Gb"

fi

echo -n "${TotalSize}${suffix}"

Code courtesy of me, Sam Schmit (<id at pt dot lu>), and

Sam's uncle Jean-Paul, who ironed out a fairly major bug in my original

code, and just generally cleaned it up.

Note that you could also just use ls -l | grep ^total | awk '{

print $2 }' because ls -l prints out a

line at the beginning that is the approximate size of the directory in

kilobytes - although for reasons unknown to me, it seems to be less

accurate (but obviously faster) than the above script.

Relative speed: this process takes between 3.2 and 5.8 seconds in /usr/bin/

(14.7 meg in the directory) on an unloaded 486SX25, depending on how much

of the information is cached (if you use this in a prompt, more or less of

it will be cached depending how long you work in the directory).

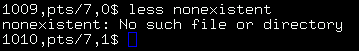

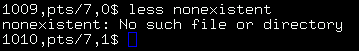

The tty command returns the filename of the

terminal connected to standard input. This comes in two formats on the

Linux systems I have used, either "/dev/tty4" or "/dev/pts/2". I've used

several methods over time, but the simplest I've found so far (probably

both Linux- and Bash-2.x specific) is temp=$(tty) ; echo

${temp:5}. This removes the first five characters of the

tty output, in this case "/dev/".

Previously, I used tty | sed -e "s:/dev/::", which

removes the leading "/dev/". Older systems (in my experience, RedHat

through 5.2) returned only filenames in the "/dev/tty4" format, so I used

tty | sed -e "s/.*tty\(.*\)/\1/".

An alternative method:

ps ax | grep $$ | awk '{ print $2 }'.

Relative speed: the ${temp:5} method takes about 0.12 seconds on an

unloaded 486SX25, the sed-driven method takes about 0.19 seconds, the

awk-driven method takes about 0.79 seconds.

Torben Fjerdingstad (<tfj at fjerdingstad dot dk>) wrote to

tell me that he often stops jobs and then forgets about them. He uses his

prompt to remind himself of stopped jobs. Apparently this is fairly

popular, because as of Bash 2.04, there is a standard escape sequence for

jobs managed by the shell:

[giles@zinfandel]$ export PS1='\W[\j]\$ '

giles[0]$ man ls &

[1] 31899

giles[1]$ xman &

[2] 31907

[1]+ Stopped man ls

giles[2]$ jobs

[1]+ Stopped man ls

[2]- Running xman &

giles[2]$

Note that this shows both stopped and running jobs. At the console, you

probably want the complete count, but in an xterm you're probably only

interested in the ones that are stopped. To display only these, you could

use something like the following:

[giles@zinfandel]$ function stoppedjobs {

-- jobs -s | wc -l | sed -e "s/ //g"

-- }

[giles@zinfandel]$ export PS1='\W[`stoppedjobs`]\$ '

giles[0]$ jobs

giles[0]$ man ls &

[1] 32212

[1]+ Stopped man ls

giles[0]$ man X &

[2] 32225

[2]+ Stopped man X

giles[2]$ jobs

[1]- Stopped man ls

[2]+ Stopped man X

giles[2]$ xman &

[3] 32246

giles[2]$ sleep 300 &

[4] 32255

giles[2]$ jobs

[1]- Stopped man ls

[2]+ Stopped man X

[3] Running xman &

[4] Running sleep 300 &

This doesn't always show the stopped job in the prompt that follows

immediately after the command is executed - it probably depends on whether

the job is launched and put in the background before jobs

is run.

Note

There is a known bug in Bash 2.02 that causes the jobs

command (a shell builtin) to return nothing to a pipe. If you try the

above under Bash 2.02, you will always get a "0" back regardless of how

many jobs you have stopped. This problem is fixed in 2.03.

Relative speed: 'jobs -s | wc -l | sed -e "s/ //g" ' takes about 0.24

seconds on an unloaded 486SX25.

The output of uptime can be used to determine both the

system load and uptime, but its output is exceptionally difficult to parse.

On a Linux system, this is made much easier to deal with by the existence

of the /proc/ file system.

cat /proc/loadavg will show you the one minute, five

minute, and fifteen minute load average, as well as a couple other numbers

I don't know the meaning of (anyone care to fill me in?).

Getting the load from /proc/loadavg is easy (thanks to Jerry Peek for

reminding me of this simple method): read one five fifteen rest

< /proc/loadavg. Just print the value you want.

For those without the /proc/

filesystem, you can use

uptime | sed -e "s/.*load average: \(.*\...\), \(.*\...\), \(.*\...\)/\1/" -e "s/ //g"

and replace "\1" with "\2" or "\3" depending if you want the one minute,

five minute, or fifteen minute load average. This is a remarkably

ugly regular expression: send suggestions if you have a better one.

Relative speed: 'uptime | sed -e "s/.*load average: \(.*\...\), \(.*\...\),

\(.*\...\)/\1/" -e "s/ //g" ' takes about 0.21 seconds on an unloaded 486SX25.

As with load, the data available through uptime is very

difficult to parse. Again, if you have the /proc/ filesystem, take advantage of it. I

wrote the following code to output just the time the system has been up:

#!/bin/bash

#

# upt - show just the system uptime, days, hours, and minutes

let upSeconds="$(cat /proc/uptime) && echo ${temp%%.*})"

let secs=$((${upSeconds}%60))

let mins=$((${upSeconds}/60%60))

let hours=$((${upSeconds}/3600%24))

let days=$((${upSeconds}/86400))

if [ "${days}" -ne "0" ]

then

echo -n "${days}d"

fi

echo -n "${hours}h${mins}m"

Output looks like "1h31m" if the system has been up less than a day, or

"14d17h3m" if it has been up more than a day. You can massage the output

to look the way you want it to. This evolved after an e-mail discussion

with David Osolkowski, who gave me some ideas.

Before I wrote that script, I had a couple emails with David O, who said

“me and a couple guys got on irc and started hacking with sed and

got this:

uptime | sed -e 's/.* \(.* days,\)\? \(.*:..,\) .*/\1 \2/' -e's/,//g' -e 's/ days/d/' -e 's/ up //'.

It's ugly, and doesn't use regex nearly as well as it should, but it

works. It's pretty slow on a P75, though, so I removed it.”

Considering how much uptime output varies depending on

how long a system has been up, I was impressed they managed as well as they

did. You can use this on systems without

/proc/ filesystem, but as he says, it

may be slow.

Relative speed: the "upt" script takes about 0.68 seconds on an unloaded

486SX25 (half that as a function). Contrary to David's guess, his use of

sed to parse the output of "uptime" takes only 0.22 seconds.

ps ax | wc -l | tr -d " " OR

ps ax | wc -l | awk '{print $1}'

OR ps ax | wc -l | sed -e "s: ::g". In

each case, tr or awk or

sed is used to remove the undesirable whitespace.

Relative speed: any one of these variants takes about 0.9 seconds on an

unloaded 486SX25.

Unix allows long file names, which can lead to the value of $PWD being very

long. Some people (notably the default RedHat prompt) choose to use the

basename of the current working directory (ie. "giles" if

$PWD="/home/giles"). I like more info than that, but it's often desirable

to limit the length of the directory name, and it makes the most sense to

truncate on the left.

# How many characters of the $PWD should be kept

local pwdmaxlen=30

# Indicator that there has been directory truncation:

#trunc_symbol="<"

local trunc_symbol="..."

if [ ${#PWD} -gt $pwdmaxlen ]

then

local pwdoffset=$(( ${#PWD} - $pwdmaxlen ))

newPWD="${trunc_symbol}${PWD:$pwdoffset:$pwdmaxlen}"

else

newPWD=${PWD}

fi

The above code can be executed as part of PROMPT_COMMAND, and the

environment variable generated (newPWD) can then

be included in the prompt. Thanks to Alexander Mikhailian

<mikhailian at altern dot org> who rewrote the code to utilize

new Bash functionality, thus speeding it up considerably.

Risto Juola (risto AT risto.net) wrote to say that he preferred to have the

"~" in the $newPWD, so he wrote another version:

pwd_length=20

DIR=`pwd`

echo $DIR | grep "^$HOME" >> /dev/null

if [ $? -eq 0 ]

then

CURRDIR=`echo $DIR | awk -F$HOME '{print $2}'`

newPWD="~$CURRDIR"

if [ $(echo -n $newPWD | wc -c | tr -d " ") -gt $pwd_length ]

then

newPWD="~/..$(echo -n $PWD | sed -e "s/.*\(.\{$pwd_length\}\)/\1/")"

fi

elif [ "$DIR" = "$HOME" ]

then

newPWD="~"

elif [ $(echo -n $PWD | wc -c | tr -d " ") -gt $pwd_length ]

then

newPWD="..$(echo -n $PWD | sed -e "s/.*\(.\{$pwd_length\}\)/\1/")"

else

newPWD="$(echo -n $PWD)"

fi